A Letter to you from

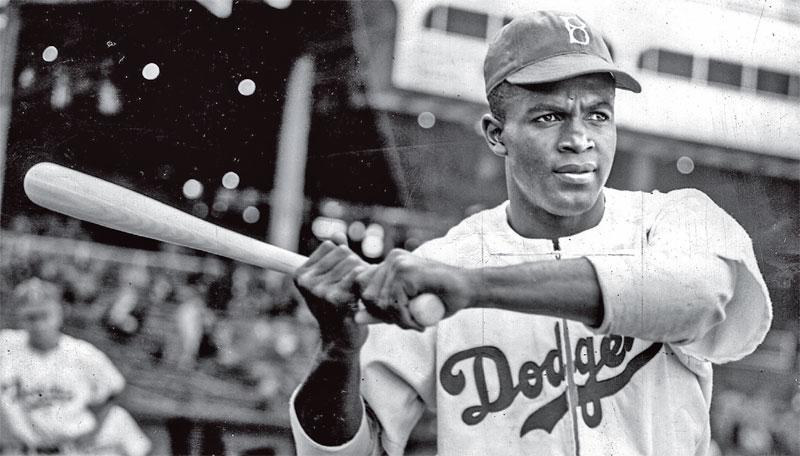

Life is not a spectator sport. If you’re going to spend your whole life in the grandstand just watching what goes on, in my opinion you’re wasting your life.” I was the fifth child born to sharecropper parents Jerry Robinson and Mallie McGriff Robinson in Cairo, Georgia. My ancestors had worked as slaves on the same property that my parents farmed. Jerry my dad, left the family to look for work in Texas when I was six months old, with the promise that he would send for us once he was settled. But Jerry Robinson never returned. (In 1921, momma received word that Jerry had died, but could never substantiate that rumour.)

After struggling to keep the farm going by herself, momma realized it was impossible. She needed to find another way to support her family, but also felt it was no longer safe to stay in Georgia. Violent racial riots and lynching’s of blacks were on the rise in the summer of 1919, especially in the south Eastern states. Seeking a more tolerant environment, momma and several of our relatives pooled their money together to buy train tickets. In May 1920, when I was 16 months old, all of us boarded a train for Los Angeles. We moved into an apartment in Pasadena, California with my uncle and his family. Momma found work cleaning houses and eventually earned enough money to buy us a house in a mostly- white neighbourhood.

We soon learned that discrimination did not limit itself to the South. Neighbours shouted racial insults at our family and circulated a petition demanding that they leave. More alarming still, we looked out one day and saw a cross burning in our yard. My momma stood firm, refusing to leave her house. With momma away at work all day, we learned to take care of ourselves from an early age. My sister Willa Mae, three years older, fed and bathed me, and took me to school with her. I was three years old when I played in the school sandbox for most of the day, while Mae peered out the window at intervals to check on me. Taking pity on our family, school authorities reluctantly allowed this unorthodox arrangement to continue until I was old enough to enrol in school at the age of five.

A rebel adult often seems like a glorious saviour, whereas a rebel child often seems like a little devil? Isn’t it! I managed to get myself into trouble on more than one occasion as a member of the “Pepper Street Gang.” This neighbourhood clique, made up of poor boys from minority groups, committed petty crimes and minor acts of vandalism. However I should thank the local minister for helping me get over this rough patch in life, he got me off of the streets and got me involved in more wholesome activities. As early as first grade, I became known for my athletic skills, with classmates even paying me with snacks and pocket change to play on their teams. I welcomed the extra food, as we Robinsons never seemed to have quite enough to eat.

I dutifully gave the money to momma. My athleticism became even more evident when I reached middle school. I was a so called natural athlete, I excelled at whatever sport I took up, including football, basketball, baseball, and track, later earning letters in all four sports while in high school. My siblings helped instil in me a fierce sense of competition. Brother Frank gave me a lot of encouragement and attended all of my sporting events. However unfortunate we may have been our family bonds were strong and kept all of us going. We loved and respected each other. Willa Mae, my sister who was also a talented athlete, excelled in the few sports that were available to girls in the 1930s. Mack, the third eldest my brother, was a great inspiration to me.

A world-class sprinter, Mack Robinson competed in the Berlin Olympics in 1936 and came home with a silver medal in the 200-meter dash. (He had come in a close second to sports legend and teammate Jesse Owens.) Upon graduation from high school in 1937, I was sorely disappointed that I hadn’t received a college scholarship, despite of my astounding athletic ability. I enrolled at Pasadena Junior College, where I distinguished myself not only as star quarterback but also as a high scorer in basketball and as a record-breaking longjumper. Boasting a batting average of .417, I was named Southern California’s Most Valuable Junior College Player in 1938! Several universities finally took notice of me, now willing to offer full scholarship for completing my last two years of college.

I decided upon the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA), mainly because I wanted to stay near my family. Death comes as a shock to everyone. It tore me apart when I lost Frank. It was a rainy day and Frank was riding his motorcycle. A truck lost its tracks and came barging on Frank, he suffered from the injuries. He was vomiting blood and covered with blood. I still vividly remember losing him. He was my greatest fan and my biggest supporter, I just went numb by his loss. I needed my getaway and focused my energy on doing well academically. Death does that to us. It changes us. I was as successful at UCLA as he had been in junior college. I was the first UCLA student to earn letters in all four sports that he played -- football, basketball, baseball, and track and field, a feat he accomplished after only one year. At the beginning of my second year, I met Rachel Isum, her and my story is a different aspect in my life. I was not satisfied with college life.

I was worried that despite getting a college education, I would have few opportunities to advance myself in a profession since I was black. Even with my tremendous athletic talent, I also saw little chance for a career as a professional athlete because of my race. In March 1941, only months before I was to graduate, Robinson dropped out of UCLA. Concerned about my family’s financial welfare, I found a temporary job as an assistant athletic director at a camp in Atascadero, California. I later had a brief stint playing on an integrated football team in Honolulu, Hawaii. I returned home from Hawaii just two days before the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbour on December 7, 1941. Drafted into the U.S. Army in 1942, I was sent to Fort Riley, Kansas, where I applied to Officers’ Candidate School (OCS). Neither I nor any of my fellow black soldiers were allowed into the program. With the help of world heavyweight champion boxer Joe Louis, also stationed at Fort Riley, I petitioned for and won, the right to attend OCS. Louis’ fame and popularity no doubt helped the cause.

I was commissioned a second lieutenant in 1943. I was approached to play on Fort Riley’s baseball team. The team policy was to accommodate any of the other teams who refused to play with a black player on the field. Here I was expected to sit those games out. Why would I want to even play in this! Unwilling to accept that condition, I refused to play even one game. Life starts to change for me at a point. It escalates and takes me to a dream I never had. In 1945, I was hired as a shortstop for the Kansas City Monarchs, a baseball team in the Negro Leagues. Playing major league professional baseball was not an option for us blacks at that time, although it hadn’t always been that way. Blacks and whites had played together in the early days of baseball in the mid-nineteenth century, until “Jim Crow” laws, which required segregation, were passed in the late 1800s. The Negro Leagues came into being in the early 20th century to accommodate the many talented black players who were shut out of Major League Baseball. It was a successful year with the Monarchs.

Among everything I got engaged to Rachel Isum back in California. Dodgers president Branch Rickey, determined to break the colour barrier in Major League Baseball, was looking for the ideal candidate to prove that blacks had a place in the majors. Rickey wanted me to play for him. He cautioned me that he would need Rachel’s support to get through the upcoming ordeal, as there was a battle ahead to defeat the racism I would face. I would face racism off the field as well, Ihad hate mail and death threats. Rickey posed me the question: could I deal with such adversity without retaliating, even verbally, for three solid years? I had always stood up for the betterment of rights, I found it difficult to imagine not responding to such abuse, but eventually realized how important it was to advancing the cause of civil rights. I agreed to do it. I started on a minor league team. As the first black player in the minors, I signed with the Dodgers’ top farm team, the M o n t r e a l Royals. O n April 9, 1 9 4 7 , f i v e d a y s b e f o r e the start of baseball season, Branch Rickey made the announcement t h at 2 8 - ye a r- o l d Jackie Robinson would play for the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Yes, it was finally my time. Not to my surprise, my new teammates had banded together and signed a petition, insisting that they would rather be traded off the team than play with a black man. It was painfully hilarious. But our manager Leo Durocher chastised the men, pointing out that I could very well lead the team to the World Series. And in 1955, we faced the Yankees once again after losing many a times. With my brazen base stealing we won against the Yankees and won the World Series. In 1957, I retired. Because dignity was much important than acceptance and recognition. I had both and what I had to lose was dignity, being 37 years of age I knew when I had to stop. I’m amazed of what life offered and what I made out of it. If you need something badly, don’t ever forget that the universe conspires for you to achieve it. Never lose hope.

Yours Truly, Jackie. (Jack Roosevelt Robinson)

Written by Devuni Goonewardene Email any feedback to devuni@ gmail.com A Letter to you from

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)