A letter to you from

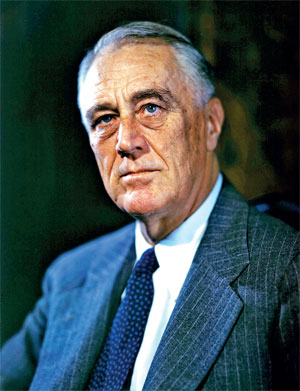

Democracy cannot succeed unless those who express their choice are prepared to choose wisely. The real safeguard of democracy, therefore, is education” Born on January 30, 1882, on a large estate near the village of Hyde Park, New York, I was the only child of my wealthy parents, James and Sara Delano Roosevelt. I was educated by private tutors and elite schools (Groton and Harvard), and early on began to admire and emulate his fifth cousin, Theodore Roosevelt, elected president in 1900.

Democracy cannot succeed unless those who express their choice are prepared to choose wisely. The real safeguard of democracy, therefore, is education” Born on January 30, 1882, on a large estate near the village of Hyde Park, New York, I was the only child of my wealthy parents, James and Sara Delano Roosevelt. I was educated by private tutors and elite schools (Groton and Harvard), and early on began to admire and emulate his fifth cousin, Theodore Roosevelt, elected president in 1900.

While in college, I fell in love with Theodore’s niece (and my own distant cousin), Anna Eleanor Roosevelt, and we married in 1905. We had a daughter, Anna, followed by five sons, one of whom died in infancy. I attended law school at Columbia University and worked for several years as a clerk in a Wall Street law firm. In 1910, I entered politics, winning a state senate seat as a Democrat in the heavily Republican Duchess County.

In 1913, President Woodrow Wilson named me the assistant secretary of the U.S. Navy. I held that post for the next seven years, traveling to Europe in 1918 to tour naval bases and battlefields after the U.S. entrance into World War I. With the support of my wife and my longtime supporter, the journalist Louis Howe, I began to return to public life, issuing statements on issues of the day and keeping up a correspondence with Democratic leaders.

Eleanor my wife, spoke publicly throughout New York State, keeping my reputation strong despite my illness; she also organized the women’s division of the Democratic Party. In 1924, I made a triumphant public appearance at the Democratic Nat i o n a l Convention to nominate New York’s Governor Alfred E. Smith for president (though Smith lost the nomination and the Democrats lost the general election). He nominated Smith again in 1928, this time successfully, and at Smith’s urgings agreed to run for governor of New York.

Smith lost to Herbert Hoover, but I won. As Governor, I grew more liberal in my policies as New York (and the nation) sank deeper into economic depression after the stock market crash of 1929. In particular, I set up the Temporary Emergency Relief Administration (TERA), which aimed at finding jobs for the unemployed, and by 1932 TERA was helping nearly one out of every 10 families in New York. Reelected as governor in 1930, I emerged as a front-runner for the Democratic presidential nomination two years later. I was able to break tradition and appeared in person in Chicago to accept the nomination, famously pledging myself to “a new deal for the American people.”

In the general election, I triumphed by an overwhelming margin over the incumbent Hoover, who had become a symbol for many people of the ongoing Great Depression. In addition, Democrats won sizeable majorities in both the House of Representatives and the Senate. By the time I was inaugurated on March 4, 1933, the Depression had reached desperate levels, including 13 million unemployed. In the first inaugural address to be widely broadcast on the radio, I declared: “This great nation will endure as it has endured, will revive and prosper; the only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” I began the momentous first 100 days of presidency by closing all banks for several days until Congress could pass reform legislation.

I also began holding open press conferences and giving regular national radio addresses in which I spoke directly to the American people. The first of these “fireside chats,” about the banking crisis, was broadcast to a radio audience of some 60 million, and would go a long way toward restoring public confidence and preventing harmful bank runs. After passage of the Emergency Banking Relief Act, three out of every four banks were open within a week.

Other key pieces of legislation during my f i r s t “Hundred Days” created some of the most important programs and institutions of the New Deal, including the Ag r i c u l t u r a l A d j u s t m e n t Administration (AAA), the Public Works Administration (PWA), the Civilian Conservations Corps (CCC) and the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). In addition to programs aimed at providing economic relief for workers and farmers and creating jobs for the unemployed, I also initiated a slate of reforms of the financial system, notably the creation of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) to protect depositors’ accounts and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to regulate the stock market and prevent abuses of the kind that led to the 1929 crash. In 1935, after the economy had begun to show signs of recovery, I asked Congress to pass a new wave of reforms, known as “Second New Deal.”

These included the Social Security Act (which for the first time provided Americans with unemployment, disability, and pensions for old age) and the Works Progress Administration. The Democratic-led Congress also raised taxes on large corporations and wealthy individuals, a hike that was derisively known as the “soak-the-rich” tax! As early as 1937, I warned the American public about the dangers posed by hard-line regimes in Germany, Italy and Japan, though I stopped short of suggesting America should abandon its isolationist policy. After World War II broke out in September 1939, however, I called a special session of Congress in order to revise the country’s existing neutrality acts and allow Britain and France to purchase American arms on a “cash-and-carry” basis. Germany captured France by the end of June 1940, and I persuaded Congress to provide more support for Britain, now left to combat the Nazi menace on its own.

Despite the two-term tradition for presidents in place since the time of George Washington, I decided to run for reelection again in 1940; I defeated Wendell L. Wilkie by nearly 5 million votes. I increased my support of Great Britain with passage of the Lend- Lease Act in March 1941 and met with Prime Minister Winston Churchill in August aboard a battleship anchored off Canada. In the resulting Atlantic Charter, we declared the “Four Freedoms” on which the post-war world should be founded: freedom of speech and expression, freedom of religion, freedom from want and freedom from fear. On December 8, 1941, the day after Japan bombed the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, I appeared before a joint session of Congress, which declared war on Japan.

I was the first president to leave the country during wartime. I spearheaded the alliance between countries combating the Axis, meeting frequently with Churchill and seeking to establish friendly relations with the Soviet Union and its leader, Joseph Stalin. Meanwhile, I spoke constantly on the radio, reporting war events and rallying the American people in support of the war effort. “The test of our progress is not whether we add more to the abundance of those who have much; it is whether we provide enough for those who have too little.”

In 1944, as the tide of war turned for the Allies, I was weary and ailing but managed to win election to a fourth term in the White House. The following February, I met with Churchill and Stalin in the Yalta Conference, where I got Stalin’s commitment to enter the war against Japan after Germany’s impending surrender. (The Soviet leader kept that promise, but failed to honor his pledge to establish democratic governments in the eastern European nations then under Soviet control.) The “Big Three” also worked to build foundations for the post-war international peace organization that would become the United Nations. After I returned from Yalta, I was so weak that I was forced to sit down while addressing Congress for the first time in my presidency. In early April 1945, I left Washington and traveled to my cottage in Warm Springs, Georgia, where I had long before established a nonprofit foundation to aid polio patients. It is common sense to take a method and try it.

If it fails, admit it frankly and try another. But above all, try something. Politics is not a joke; no one seems to realize it these days. The jokes are finally on us, when humans with the tendency to misuse all we’ve got get selected. We may laugh at what we see, but ultimately the government is for the people and by the people.

Who are the real jesters now? Franklin Delano Roosevelt 32nd President of the United States of America

Written by Devuni Goonewardene

Email any feedback to [email protected]

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)