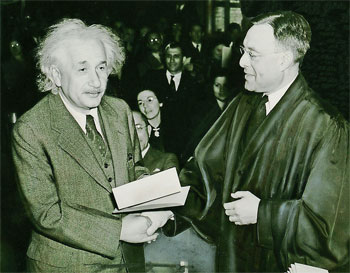

ALBERT EINSTEIN: The slow learner to a Genius

(1879-1955) He was the pre-eminent scientist in a century dominated by science. The touchstones of the era--the Bomb, the Big Bang, quantum physics and electronics all bear his imprint The embodiment of pure intellect, the bumbling professor with the German accent, a comic cliche in a thousand films. Instantly recognizable, like Charlie Chaplin’s Little Tramp, Albert Einstein’s shaggy-haired visage was as familiar to ordinary people as to the matrons who fluttered about him in salons from Berlin to Hollywood. Yet he was unfathomably profound the genius among geniuses who discovered, merely by thinking about it, that the universe was not as it seemed. Even now scientists marvel at the daring of general relativity. But the great physicist was also engagingly simple, trading ties and socks for mothy sweaters and sweatshirts.

(1879-1955) He was the pre-eminent scientist in a century dominated by science. The touchstones of the era--the Bomb, the Big Bang, quantum physics and electronics all bear his imprint The embodiment of pure intellect, the bumbling professor with the German accent, a comic cliche in a thousand films. Instantly recognizable, like Charlie Chaplin’s Little Tramp, Albert Einstein’s shaggy-haired visage was as familiar to ordinary people as to the matrons who fluttered about him in salons from Berlin to Hollywood. Yet he was unfathomably profound the genius among geniuses who discovered, merely by thinking about it, that the universe was not as it seemed. Even now scientists marvel at the daring of general relativity. But the great physicist was also engagingly simple, trading ties and socks for mothy sweaters and sweatshirts.

He was a cartoonist’s dream come true. Einstein’s galvanizing effect on the popular imagination continued throughout his life, and after it. Fearful his grave would become a magnet for curiosity seekers, Einstein’s executors secretly scattered his ashes. But they were defeated at least in part by a pathologist who carried off his brain in hopes of learning the secrets of his genius. Only recently Canadian researchers, probing those pickled remains, found that he had an unusually large inferior parietal lobe a center of mathematical thought and spatial imagery and shorter connections between the frontal and temporal lobes. Unlike the avuncular caricature of his later years who left his hair unshorn, helped little girls with their math homework and was a soft touch for almost any worthy cause, Einstein is emerging from these documents as a man whose unsettled private life contrasts sharply with his serene contemplation of the universe. He could be alternately warmhearted and cold; a doting father, yet aloof; an understanding, if difficult, mate, but also an egregious flirt. “Deeply and passionately concerned with the fate of every stranger,” wrote his friend and biographer Philipp Frank, he “immediately withdrew into his shell” when relations became intimate.

WAS EINSTEIN A SLOW LEARNER AS A CHILD?

Einstein was slow in learning how to speak - his parents even consulted a doctor. He also had a cheeky rebelliousness toward authority, which led one headmaster to expel him and another to amuse history by saying that he would never amount to much. But these traits helped make him a genius. His cocky contempt for authority led him to question conventional wisdom. His slow verbal development made him curious about ordinary things such as space and time that most adults take for granted. His father gave him a compass at age five, and he puzzled over the nature of a magnetic field for the rest of his life. And he tended to think in pictures rather than words.

WAS EINSTEIN LEARNING DISABLED?

Some researchers claim to detect in Einstein’s childhood a mild manifestation of autism or Asperger’s syndrome. Even as a teenager, Einstein made close friends, had passionate relationships, enjoyed collegial discussions, communicated well verbally and could empathize with friends and humanity in general.

DID EINSTEIN THINK IN PICTURES RATHER THAN WORDS?

Yes, his great breakthroughs came from visual experiments performed in his head rather than the lab. They were called Gedankenexperiment thought experiments. At age 16, he tried to picture in his mind what it would be like to ride alongside a light beam. If you reached the speed of light, wouldn’t the light waves seem stationery to you? He knew that math was the language nature uses to describe her wonders, so he could visualize how equations were reflected in realities - for the next ten years he wrestled with this thought experiment until he came up with the special theory of relativity.

WHAT WAS EINSTEIN’S MIRACLE YEAR?

In 1905, Einstein had graduated from college but had not been able to get a doctoral dissertation accepted or get an academic job. So he was toiling six days a week as a third-class examiner in the Swiss patent office. During his spare time, he produced four papers that upended physics. The first showed that light could be conceived as particles as well as waves. The second proved the existence of atoms and molecules. The third, the special theory of relativity, said that there was no such thing as absolute time or space. And the fourth noted an equivalence between energy and mass described by the most famous equation in all of physics,

In 1905, Einstein had graduated from college but had not been able to get a doctoral dissertation accepted or get an academic job. So he was toiling six days a week as a third-class examiner in the Swiss patent office. During his spare time, he produced four papers that upended physics. The first showed that light could be conceived as particles as well as waves. The second proved the existence of atoms and molecules. The third, the special theory of relativity, said that there was no such thing as absolute time or space. And the fourth noted an equivalence between energy and mass described by the most famous equation in all of physics,

E=mc2.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)